The International Day of Family Remittances is observed today as the World Bank predicts a sharp drop of 20% in the vital funds 200 million migrant workers send their 800 million family members back home.

Essential to food systems, in Europe alone it’s estimated that Covid-19 lockdown will see one million less seasonal agricultural workers. Migrants in the United States of America make up 10 percent of crop farmworkers. The US seafood industry, particularly in Alaska, relies on more than 20,000 migrants annually. In the UK 80,000 seasonal agricultural workers are needed each year, according to the Office for National Statistics.

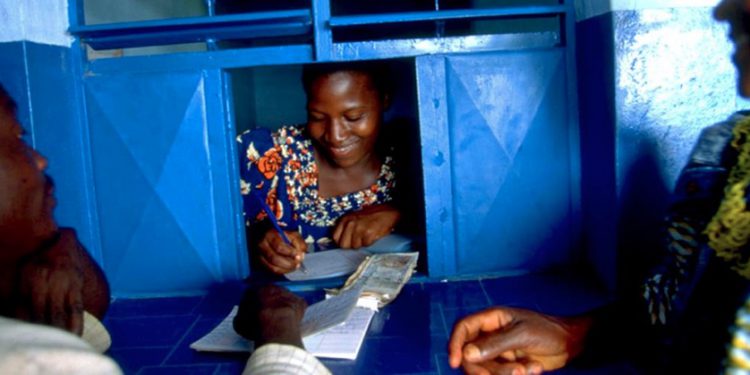

Migrant workers have an important impact on food systems in their own countries, given that 60% of remittances go to family in rural areas, subsidising agriculture there. All remittances help families buy food in some of the world’s poorest countries.

Released in April, the World Bank’s report discussed the impact on low to middle-income countries. A fall in remittances of 20 per cent is a drop to $445 billion, from $554 billion in 2019. It said remittances are an economic lifeline, more reliable than foreign investment. They make up more than one fifth of Gross Domestic Product in countries such as El Salvador and Nepal.

Labour shortages will impact agricultural value chains, affecting supply and prices

Migrant workers tend to share rent, spend savings or skip a meal in order to keep payments going or to pay more during times of hardship in their home countries. This will be important in many countries which could see a reduction in foreign aid, due, again to the pressure of the richer economies contracting in response to Covid-19.

Also in April, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization reported on the impact of Covid-19 on migrant workers, highlighting their substantial role in agri-food systems. Much of this is under-reported because so many are employed informally. The report said labour shortages will have an impact on agricultural value chains, affecting food availability and market prices globally.

Shortages of labour could disrupt production, as well as the processing and distribution of food. Concerns are also emerging about shortages of migrant workers during planting and harvesting.

The report said governments should respond by protecting workers at the workplace, expanding temporary work permits and making sure travel is safe within and across countries. They should match labour demand and supply, protecting livelihoods and supporting the most vulnerable.