The last of Isobel’s elders have died; the people who took canoes, even swam from island to island. We explore the breathtaking artwork Isobel is now culturally responsible for. Catch up with the first part of this long-read here. The third and final part is here.

It’s a huge responsibility. Some elders swam from island to island – with no fear of the crocodiles and sharks; they walked inland from Wijingarra Butt Butt to the Gibb River and into Derby.

The grief is difficult enough, having to cope with the death of those you have loved, whose job was to protect you, explain the world and guide you.

But the loss also opens up the reality of the future, the burden on Isobel to respect her elders’ wishes, and protect their land and their ways.

I don’t want to use the word proud because this is applied in such a patronising fashion generally – “a proud people” sounds incredibly condescending.

Isobel is superior – in the best sense of the word. Her confidence, her gravitas, her complete acceptance of the enormity of responsibility for her clan, her devotion to her country and people is on a scale you might imagine of fairy-tale European nobility.

Isobel’s ways are not adopted; they have been inculcated in her from birth.

“The elders, the munnumburra, told me to be strong. They told me to be humble.”

The elders always told her things like don’t let yourself be turned from laws, or speak for another’s country, don’t forget your tribal relationships, always remember who you are.

“The elders, the munnumburra, told me to be strong,” she says. “They told me to be humble. I spent a lot of time talking with the man I called Daddy (a very important elder called Paddy Neowarra) before he died. He was clear that I had to be able to work with the almara, the foreigners, and also to carry our ways with me. We carry them in our heads. We carry them in our stomachs. This way they can never be lost.

“Our ways are for everyone to share, not just for us Worrora. It’s for everyone. Almara too. We have to live well together.

“And things are getting better. White people are interested in our culture and laws now. The elders would be happy about this.

“When it comes to our ways, we really believe in these things. Everything is mamaa to us – it’s sacred.

“We know that bad things will happen if you go against the proper ways. Like our stories that said heavy rains will flood and destroy everything. All this is true.”

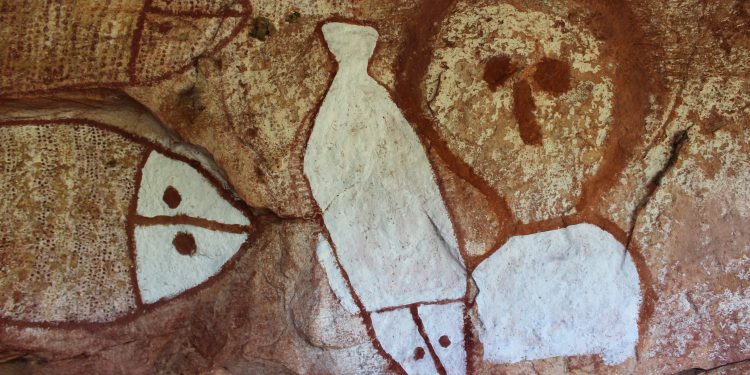

These beliefs are illuminated in the ancient cave art across Isobel’s estate, of which she is custodian. Among the owls, dolphins, whales, fish, her totem spirit the stingray, and other animal images, are cyclones and whirlpools.

The dramatic local tides vary by as much fourteen metres, causing incredible whirlpools and waterfalls offshore around the Montgomery islands or Yowjab.

In this part of the world there is a Dry season – during which I’m visiting – and a Wet season so severe that cyclones are regular visitors, bringing torrential rain and, as I see along the coast, transporting massive trees and turning them into huge logs of driftwood.

“Wanjinas are painted without mouths because there are things never spoken”

Isobel’s country, along with other parts of the Kimberley, is famous for its sacred Wanjinas – creation gods – sometimes painted with cumulus clouds around their heads.

Discussing these highly sacred images reflexively causes anxiety, as Isobel was raised to respect these gods so greatly that the subject was generally avoided.

“My mother tried never to say the word Wanjina, and if she ever had to say it, she whispered it,” says Isobel. “They are painted without mouths because there are things never spoken, things you should never know. Not until the right time. Otherwise, you will lose your mind. It will make you go completely insane.

“Sometimes, even when you visit the sites, it’s the wrong time, the stories will get stuck. The knowledge is frozen. It’s okay. You just wait, and the right time will come.”

History and the intense interest in Wanjinas by foreigners has forced Isobel’s people to speak about them, though they would not have in the past, not to anyone outside their tribal kinship and belief system.

Isobel shares a story of her old people – the one story that never changes: The Wanjinas created everything in the Lalai, the Dreamtime, including all the laws of nature and society.

This determined which clans belong in which territories, the totem animals, the relationships between all things, including rules on marriages – highly elegant regulations that have successfully protected against inbreeding among small populations for tens of thousands of years.

Isobel and her son Neil explain that the Wanjinas had to return to earth after the Dreamtime, the Lalai, because tribal people were ignoring the laws.

They reset the laws with humans, then they left their images in the caves, where they can be seen in the paintings, touched up over thousands of years. Other, select clan members are asked to touch up the paintings when the time comes; it’s always done by men. Isobel’s Arraluli clan doesn’t refresh its own paintings.

“I’m warning the spirits a foreigner is coming. Don’t take it the wrong way”

Before approaching her sacred sites, Isobel calls out to the spirits in Worrora to warn them.

“I’m telling them a foreigner is coming through,” she says. “Don’t take it the wrong way though, I would say the same thing about an Aboriginal person who’s not part of my clan.”

After we leave each site, Isobel makes sure that smoking eucalypt branches are waved around us, from head to toe, to keep the spirits happy, keep the bad spirits away.

Isobel belongs to one of a number of clan groups who make up the Worrora tribe, each with their own estate. The Worrora are also connected, via shared Wanjina law, to the Wanambul tribe to the north and the Ngarinyin tribe inland and to the south. The bonds between all three tribes are close, and they comfortably speak each other’s languages.

Her clan, which descends through her grandfather, who had only daughters, and with all males of the descendent line dead, has been determined by patrilineal descent. Isobel has six children by a tribal Ngarinyin man. Now dead, his name is not spoken.

“But I also have a promise husband and he’s still alive. We all get one,” Isobel explains.

“We don’t have to marry each other if we don’t want to, but we do have to look after each other. My promise husband Neville’s a Worrora man. He’s in his fifties and we still look out for each other. I can go up to Neville any time and tell him what to do. He’ll do it.”

“We recognise each other by seeing the forehead first”

The Wanjina’s law means everyone is clear about who they have responsibility for. The three tribes recognise each other immediately because they “see the forehead first”. In the course of conversation, and even in meaningful silences, it tilts forward frequently.

“It’s how we say hello.” Isobel smiles. “Look. There’s no word for it, we just do this.” And she bows slightly, eyes lowered and forehead upright.

“I will always recognise one of my people. I’ll know how I am related to them, by birth or by skin, which is clan, by marriage, and what my obligation to them is. I keep track of hundreds of people this way.

“And I also respect other people’s land. We all know where we belong. If I’m going through someone else’s territory, I tell them don’t worry, I’ve got my land, I’m just passing, and then they can relax.

“We’re spirit people. Everyone in this tribe who believes in their culture believes that their spirit comes from this country”

“Our clans are connected directly to land. Because I’m Arraluli, my estate is the Lulim – it’s always been this way.

“We’re spirit people. Everyone in this tribe who believes in their culture believes that their spirit comes from this country. A father will know the spirit of his child. Water is very sacred. The spirits of babies are usually associated with fresh water. It could come in a dream, or maybe in an animal they hunt, and usually the child will have that marking. If it was a kangaroo and they speared it, then the child will be born with that mark, so we know that’s the spirit.”

The relationship between knowledge, obligation and social order is more sophisticated than anything I’ve experienced in Japan, or the Middle East, let alone Italy or France. In country, conduct is highly regulated. Men and women don’t spend a lot of time together; we each have different tasks to be getting on with. The way we speak with one another, whether or not, or how, we might touch, is all subject to a correct approach.

There’s a calf whale and it’s mother, a turtle and a Wanjina, Isobel’s totem a huge stingray, fish, dugong and owls.

When the time is right to visit a sacred cave near Wjingarra Butt Butt, Isobel’s sons Neil and Bart bring a rake. They might sometimes resist chores around the camp, like washing the dishes, but they don’t need to be asked to do this job. They will sweep the ground inside the cave to keep it looking tidy, and also so that when Isobel returns she will be able to date the fresh tracks. She’s creating a time stamp, the way they did in the old days.

Two rocks naturally form a chair with a back, inside. “I like to think my grandmother sat here like this,” Isobel smiles, as she takes up the position. “It’s perfect for her, see.”

Images applied across rounded, under-hanging rocks, run almost the length of the narrow cave; the impact of these shifting perspectives is mesmerising.

There’s a calf whale and it’s mother, a turtle and a Wanjina, Isobel’s totem a huge stingray, fish, dugong and owls.

She explains that the munnumburra, the elders, treated cave visits ritualistically sometimes. You might only visit during a correct moon. You might camp for three days first, before it was time to go into the cave.

When the time was right, you laid on the ground, looking up at the paintings across the cave, and allowed yourself to dream, connecting to the gods and stories.

This cave tells a fish, or jaiya Dreaming connected to the creation deeds of the Wanjinas

The remarkable Numbree or Raft Point is arrived at by boat, its red cliffs rising more impressively than the scale of any cathedral. It’s impossible not to be awestruck.

Here we landed the boat to meet tourists from a passing cruise ship. Isobel’s daughter Naomi greets the visitors, daubing red ochre on each cheek. This signifies to the spirits that the tourists are welcome guests.

We walk them up into the hill, overlooking the sea, to a sacred cave, where son Neil and Isobel explain the paintings.

Neil encourages visitors to lie on their back, looking up at the images, letting the mind wander as the art plays across the rocks above.

Breathtaking images here include the Gwion, incorrectly called Bradshaw paintings in the past, after the explorer Joseph Bradshaw. For many years white people offensively said Gwion images belonged to an “earlier mystery race”, but this has been systematically debunked by western science as well as by the tribal elders.

The Gwion is joined in Numbree by a half-moon Wanjina, watching over a fishing expedition. This cave tells many stories. It’s a fish, or jaiya Dreaming connected to the creation deeds of the Wanjinas, when they made the land and nature within it.

Neil and Isobel explain that a great flood wiped out most of the people, along with the wurnan – the social legal system – and Wanjinas returned to earth to re-set wurnan. This wurnan included the contract that only appropriate men would retouch the sacred cave images.

Some images were retouched by appropriate tribal members just five years ago. An earlier touching up of these images was recorded by filmmakers in the ’70s. There’s a snippet here.

The cave paintings here are Paleolithic, predating Lascaux in France or Altamira in Spain

Some images haven’t been refreshed and look faded. It’s agreed that the original cave paintings here are Paleolithic, predating Lascaux in France or Altamira in Spain. It is explained to tourists who visit here, that this very area has been dated as having continuous occupation for at least 50,000 years.

The relationship between the art Isobel is responsible for, and the outside world, is a complicated one.

Arguments over ownership of the paintings bogged down her elders while they defended their heritage for decades. While they were thus occupied, the vulnerability of Isobel’s tribal culture was exploited.

For those who have broken the Wanjina laws, there is a deep regret and sadness at the inevitable consequences suffered; unexplained deaths and serious accidents.

Near the entrance to one cave, Isobel points out a gap in a tree trunk, where layers of bark have been removed. “You see here, that’s been used as a baby cradle,” she explains. “We call it angham. You can see where someone pulled it out.”

Isobel can tell where a beehive, full of honey, was removed by an ancestor

Clues such as this, left by old clan members, are found throughout the estate.

Another time, walking along a rocky river bed near Wijingarra Butt Butt that fills during the Wet season, we come across a certain rock fig tree that Isobel can see has had a beehive, full of honey, removed, and a soap tree that ants have built their nests around.

Our walks involve stopping to decide what the bird and animal tracks are telling us, discussing what animals the excrement we find might be from, observing birds and animals.

“But we were lazy gardeners,” Isobel laughs. “We just burnt the land, that’s so much easier.”

Before moving on from a camp, Isobel’s nomadic family performed controlled burning, to dispose of waste and regenerate the landscape. Now, each year, when the family leaves Wijingarra Butt Butt, the state fire authority does controlled burning around the site with the help of tribal rangers from Isobel’s community, who have done ranger training.

This creates a firebreak around the site ahead of the tinderbox heat, which soars toward the end of each year, just before the weather breaks in the Wet season.

- Head to the third and final part of this series here.

If you would like to know more about what Isobel is doing in her country head to Lulim Foundation or you can contact her at arraluli@gmail.com.

You can also check out her whale advocacy web page here.