Governments must urgently adopt policies allowing smallholder farmers to benefit from genome-edited crops, according to scientists writing in Nature Magazine.

They say labelling rules should be framed in a harmonised global system of transparent, science-based risk consideration.

New traits in food should be included on a label if they introduce new allergens or toxins, or fundamentally change the composition of the food.

But the production method, such as whether the crop is the result of gene editing, should not be part of mandatory labelling requirements.

Led by Kevin Pixley of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), in Texcoco, Mexico, the researchers’ Comment piece says, “Ensure that genome-editing technology remains accessible to those who will use it to democratise its benefits, particularly for resource-poor farmers and consumers in low- and middle-income countries.”

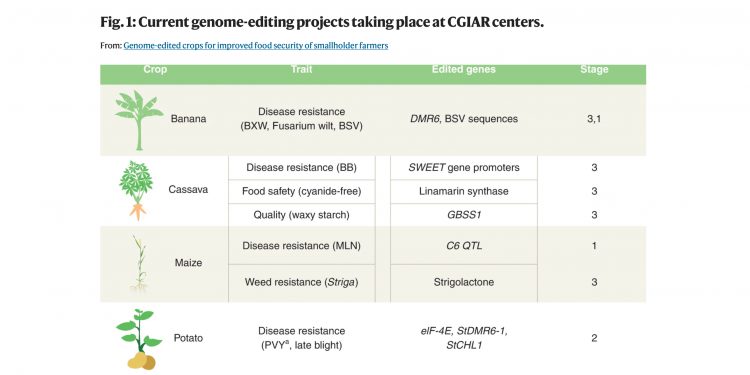

Genome-editing technologies can reduce the costs of breeding and accelerate the delivery of new varieties to farmers, they write.

But the future of genome-edited crops is contingent on effective governance.

“If considered transgenic, genome editing research would be managed by multinational seed companies”

The faster speed and lower cost of developing varieties by using genome editing could democratise their use by researchers at public universities and scientific institutions, including for orphan or commercially minor crops.

This could benefit smallholder farmers and consumers.

But this could become difficult if the products of genome editing are instead regulated in the same way as transgenics, like genetically modified crops, in which one or more DNA sequences from another species have been introduced by artificial means.

In that case, the research and varieties would be highly managed and controlled by multinational seed companies, and remain mostly unavailable to smallholder farmers, the writers say.

In 2018, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that genome-edited crops should be considered as transgenics in the EU.

The EU stance on transgenics discouraged developing countries that trade with the EU from using these varieties.

The same could happen with genome-edited crops.

The CJEU judgment that classified gene-edited crops as transgenics was at odds with an emerging consensus among western-hemisphere countries that saw no justification in regulating crops as transgenics if they were edited with only single-point mutations.

“Genome-edited crop risks should be considered in the context of plant breeding”

The United Kingdom began freeing itself from the CJEU ruling on gene-edited crops soon after its exit from the EU. Other countries, including Japan, signalled their intent not to classify most genome-edited crops as transgenic.

China’s position on the regulation of genome-edited crops could also prove decisive for global harmonisation. China has invested heavily in genome editing, and by 2019 it was publishing twice as many related agricultural papers as the United States.

One mechanism for transparency is an easily accessible registry through which developers of genome-edited crops can disclose the use of genome-editing technologies and meet public interest about how specific foods are produced.

Such registries should remain separate from the patent and regulatory risk-assessment systems. One such registry, developed by The Center for Food Integrity through their Coalition for Responsible Gene Editing in Agriculture.

The authors say the risks of genome-edited crops should be considered alongside their benefits, and in the context of plant breeding.

Traditional conventional breeding is not free of risks, such as unintended increased levels of toxic alkaloids in fava bean and potato, introduction of disease susceptibility, or the reduction of protein content when breeding for increased grain yield.

Mutations occur spontaneously with every generational advance, giving rise both to favorable and unfavorable (sometimes lethal to the variety, such as chlorophyll deficiency) alleles that drive natural selection for fitness and enable farmer- and consumer-guided selection for preferred traits.

These risks provide a baseline and context to assess the risks of genome-edited plants.