The Economist looks at a new report on the economics of biodiversity commissioned by the British government, and produced by Partha Dasgupta of the University of Cambridge.

Breathable air, drinkable water and tolerable temperatures and the complex ecosystems that maintain them, tend to be taken for granted. This is more than a mere analytical oversight, reckons.

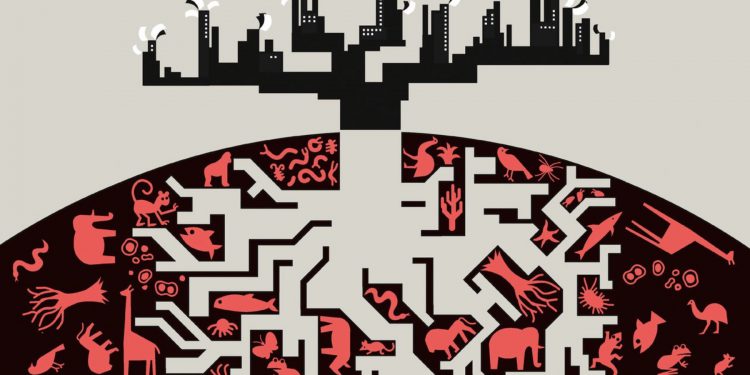

By overlooking the role nature plays in economic activity, economists underestimate the risks from environmental damage to growth and human welfare.

It makes the hard-headed case that services provided by nature are an indispensable input to economic activity. Some of these services are relatively easy to discern: fish stocks, say, in the open ocean. Others are far less visible: such as the complex ecosystems within soil that recycle nutrients, purify water and absorb atmospheric carbon. These are unfamiliar topics for economists, so the review seeks to provide a “grammar” through which they can be analysed.

The report features its own illustrative production function, which includes nature. The environment appears once as a source of flows of extractable resources (like fish or timber).

But it also shows up more broadly as a stock of “natural” capital from which humans derive “regulating and maintenance services”: the work of environmental cycles that refresh the air, churn waste products into nutrients, and keep global temperatures hospitable, among other things.

With this new production function in hand, economists can properly account for nature’s contributions to growth. Functions that omit nature misattribute its benefits to productivity, exaggerating human capabilities.

The inclusion of natural capital enables an analysis of the sustainability of current rates of economic growth.

As people produce GDP, they extract resources from nature and dump waste back into it. If this extraction and dumping exceeds nature’s capacity to repair itself, the stock of natural capital shrinks and with it the flow of valuable environmental services.

Between 1992 and 2014, according to a report published by the UN, the value of produced capital (such as machines and buildings) roughly doubled and that of human capital (workers and their skills) rose by 13%, while the estimated value of natural capital declined by nearly 40%.

The demands humans currently place on nature, in terms of resource extraction and the dumping of harmful waste, are roughly equivalent to the sustainable output of 1.6 Earths (of which, alas, there is only the one).

To reduce these demands without slowing growth would be a monumental task. Between 1992 and 2014, Professor Dasgupta estimates, the efficiency with which humans transformed natural capital into GDP grew at about 3.5% a year. To stop natural capital declining by 2030 while maintaining current growth trends, however, would require growth in efficiency of about 10% a year.