An Economist feature says Tony’s Chocolonely’s chunky bars are aimed at the young and affluent, who expect firms to do more for society than simply pay their taxes. According to research by McKinsey, a consultancy, nine out of ten consumers born between 1995 and 2014 – known as Generation Z – reckon companies have a responsibility to address environmental and social issues.

In the age of cancel culture, brands that take the moral high ground are playing a risky game. Last year Oatly, an oat-milk producer that bills its wares as a more sustainable alternative to dairy, was boycotted by some customers after part of the company was sold to Blackstone, a private-equity firm whose ceo and co-founder, Steve Schwarzman, had donated money to Republican politicians, including Donald Trump. A Twitter thread, also mentioning Oatly, alleged that another company Blackstone had a stake in was involved in deforestation in the Amazon. (Blackstone denies the allegations.)

Tony’s recently made the wrong sort of headlines, too, after Slave Free Chocolate, a pressure group, dropped it from its list of ethical producers. The beans used in Tony’s bars are processed by Barry Callebaut, a company that is being taken to court in America by representatives of eight former child- workers on cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast. On its website, Barry Callebaut pledges to “eradicate child labour from our supply chain” by 2025.

Ayn Riggs, director of Slave Free Chocolate, thinks Tony’s ethical mission is merely a way to sell more bars.

“To me it just smacks of using a bad situation to market your product – ‘buy me, I’m slave free’ – when in fact nothing is changing for these farmers in these countries,” she says. Tony’s says it has always been open about its relationship with Barry Callebaut and that the best way to reform an imperfect system is from within.

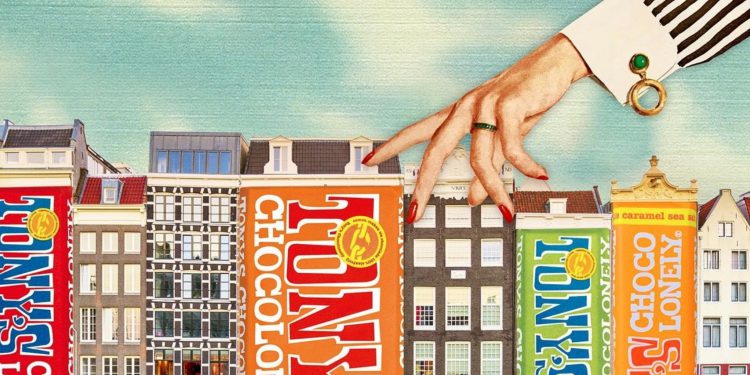

The recent threats of a boycott probably won’t hurt the business too much. Tony’s Chocolonely is the fastest-growing chocolate brand in Britain and its international market is expanding fast.