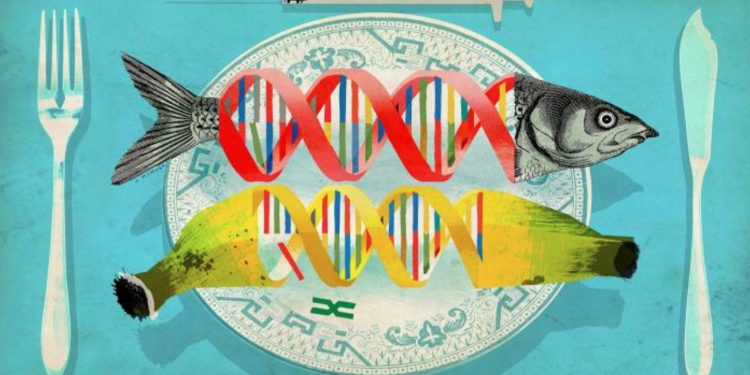

Camilla Cavendish writes in the Financial Times that new gene-editing techniques could transform farming, and play a vital role in combating climate change, but they are still widely shunned as creating “Frankenfoods”.

In February, the Co-op supermarket reaffirmed its ban on genetically engineered ingredients from its product range, in response to concerns that the UK government wants to make gene editing easier post-Brexit.

Loosening such restrictions could usher in techniques to combat disease and grow crops with higher yields to feed the world.

The Cavendish banana dominates world production but is now on the verge of being wiped out by a new strain of Panama disease, a fungus which has already killed off the only other banana which looked and tasted like the Cavendish, the Gros Michel.

In some countries where farmers rely on these crops to earn a living, the situation is desperate: Colombia declared a national state of emergency in August 2019, when Panama disease was discovered on its banana farms.

With pesticides unable to combat the fungus, it seems that the only way to save the Cavendish banana is to alter its genome.

Such genetic tweaking seems unnatural. But the Cavendish banana itself is unnatural, bred as a clone to make each generation genetically identical.

In fact, almost nothing we eat is truly “natural”: every crop and animal we consume derives from centuries of breeding.

With climate change the next big threat, the huge carbon footprint of farming must be addressed. Genetic engineering offers the possibility of ending dependence on fertilisers which use fossil fuels, and of making crops more resilient. It will allow us to engineer rice to produce less methane and ultimately grow meat in the laboratory, which would drastically reduce the number of intensively farmed animals.

The UK’s Rothamsted Research crop centre is testing camelina plants genetically modified to express the same kind of Omega-3 oils found in fish. “Golden Rice” is a GM crop with added genes for the chemical beta-carotene, in an attempt to make it provide more vitamin A.

In the 1990s, I supported environmentalists who opposed GM. Today, the scientists I speak to seem to inhabit a different world to the days of “atomic gardening”.

Further reading:

- Global approach to labelling needed for gene-edited crops

- Editing: a Disin-gene-uous business?

- EU Commission at odds with Parliament over GM